In May, 1990, my then-girlfriend and I quit our jobs, put our stuff into storage, and started driving cross-country. Over the next 3 months we wandered all over the Western US and Canada, partly vacationing, partly looking for a place to live. Finally in mid-August we parked it in Boulder, Colorado, and over the next few weeks, while she registered for business school classes at the University of Colorado, I zipped around the Boulder-Denver metro area on a couple of hundred errands associated with securing an apartment and a job.

We’d been through the area earlier in the summer, so it wasn’t entirely new to me, but as I drove around the neighborhoods and strip malls of the Front Range I kept noticing these funny black & white “crows” everywhere; growing up in New England, I’d never seen a Magpie before.

We’d been through the area earlier in the summer, so it wasn’t entirely new to me, but as I drove around the neighborhoods and strip malls of the Front Range I kept noticing these funny black & white “crows” everywhere; growing up in New England, I’d never seen a Magpie before.

In the 2 decades since, Magpies have been around pretty much everyplace I’ve lived*.  I drive, walk, run and bike past them routinely. For months in the summer, when so much is going on, I won’t really notice them, but when the cold settles in and the branches are bare and the songbirds have largely flown South or just shut up, I suddenly notice them again**, going about their business. Magpies aren’t the most beautiful or elegant or melodious or charming of the birds in my life, but they’re the most constant, some of the most common, and arguably, the most interesting. They’ve been on my “List” since day one of this project, and in some sense I think they’ve been on the “List” since before there was a list or a project, or even blogs, at all. They’ve been on the “List” since I parked it in Boulder almost 20 years ago, and it’s time to check them out.

I drive, walk, run and bike past them routinely. For months in the summer, when so much is going on, I won’t really notice them, but when the cold settles in and the branches are bare and the songbirds have largely flown South or just shut up, I suddenly notice them again**, going about their business. Magpies aren’t the most beautiful or elegant or melodious or charming of the birds in my life, but they’re the most constant, some of the most common, and arguably, the most interesting. They’ve been on my “List” since day one of this project, and in some sense I think they’ve been on the “List” since before there was a list or a project, or even blogs, at all. They’ve been on the “List” since I parked it in Boulder almost 20 years ago, and it’s time to check them out.

*The notable exception was a 3 year period in the early 1990’s when I lived in Evergreen, Colorado, in a Ponderosa forest at ~8,000 feet. Magpies were replaced by another corvid up there, the Stellers Jay.

**And in fact this is the time of year when I always start re-noticing corvids again of all sorts. I mentioned last week the Stellers Jays hanging out in Mill Creek Canyon; in past autumns they’ve been common in Dry Creek. And there are dozens of Scrub Jays (pic right) right now across the street from the zoo, in the scrub oaks around the Shoreline trailhead.

**And in fact this is the time of year when I always start re-noticing corvids again of all sorts. I mentioned last week the Stellers Jays hanging out in Mill Creek Canyon; in past autumns they’ve been common in Dry Creek. And there are dozens of Scrub Jays (pic right) right now across the street from the zoo, in the scrub oaks around the Shoreline trailhead.

All About Magpies

Magpies look like Crows because they’re closely-related to them, part of the Corvid family we keep bumping into. They’re super-common throughout the Western US, but (strangely) mostly absent from the East, and elsewhere they span the Northern hemisphere, stretching clear across Eurasia. Here in the US they have somewhat of a bad rap. They’re loud; their decidedly non-melodic squawks are harsh and make for a rough wake-up call, especially in Winter, when they often roost communally. They regularly prey upon the eggs and nestlings of other birds-especially songbirds, and they’re even rumored to peck at and enlarge open sores on the backs of livestock.

Magpies look like Crows because they’re closely-related to them, part of the Corvid family we keep bumping into. They’re super-common throughout the Western US, but (strangely) mostly absent from the East, and elsewhere they span the Northern hemisphere, stretching clear across Eurasia. Here in the US they have somewhat of a bad rap. They’re loud; their decidedly non-melodic squawks are harsh and make for a rough wake-up call, especially in Winter, when they often roost communally. They regularly prey upon the eggs and nestlings of other birds-especially songbirds, and they’re even rumored to peck at and enlarge open sores on the backs of livestock.

All of these things are true, but in their defense they’re dedicated spouses and parents, hard-working and industrious providers, and arguably way smarter than any of the pretty little songbirds we oo and ah about at our feeders.

Magpies are omnivorous generalists; they eat berries, seeds, nuts, carrion, small rodents, and lots and lots of insects, which comprise a larger portion of their diet- it’s believed- than they do any other corvid. And yes, they also regularly eat eggs and fledglings of other birds. But in fairness so do lots of other birds, including many we greatly admire, such as eagles and hawks, and in fact the eggs and fledglings of Magpies are regularly preyed upon in turn by hawks, owls and ravens, a factor that strongly influences the architecture of their nests as we’ll see in a moment. (And besides, most of the people I know eat plenty of mammals, so give ‘em a break already.) Unusual for birds in general, but not for carrion-eating birds, Magpies seem to have a well-developed sense of smell.

Magpies are omnivorous generalists; they eat berries, seeds, nuts, carrion, small rodents, and lots and lots of insects, which comprise a larger portion of their diet- it’s believed- than they do any other corvid. And yes, they also regularly eat eggs and fledglings of other birds. But in fairness so do lots of other birds, including many we greatly admire, such as eagles and hawks, and in fact the eggs and fledglings of Magpies are regularly preyed upon in turn by hawks, owls and ravens, a factor that strongly influences the architecture of their nests as we’ll see in a moment. (And besides, most of the people I know eat plenty of mammals, so give ‘em a break already.) Unusual for birds in general, but not for carrion-eating birds, Magpies seem to have a well-developed sense of smell.

Serious Nests

Magpies live about 5 or 6 years in the wild*, and like most Corvids, are committed monogamists, mating for life**. But while pairs are closely-associated during breeding season (March-July), they’re a bit less so during the off-months. Every year, as early as January, romance seems to be rekindled and the pairs become closer again. As breeding season approaches, Magpies can often be seen flying about with twigs in their mouths, indicating that nest-building has begun.  Their nests are the most impressive nests in Western suburbia, positioned in large trees 25’+ above ground, up to 4’ high and 3.5’ wide. And not only are they big- they’re roofed, with thick, protective domes covering them from above.

Their nests are the most impressive nests in Western suburbia, positioned in large trees 25’+ above ground, up to 4’ high and 3.5’ wide. And not only are they big- they’re roofed, with thick, protective domes covering them from above.

*Which isn’t all that long for corvids. Ravens for example can live for over 40 years in the wild, and Blue Jays up to 17.

**Although Magpies, like most corvids and in fact the majority of monogamous bird species, do “cheat” fairly frequently, engaging what biologists call “extra-pair copulations.” I blogged about this at length in last month’s Blue Jay post.

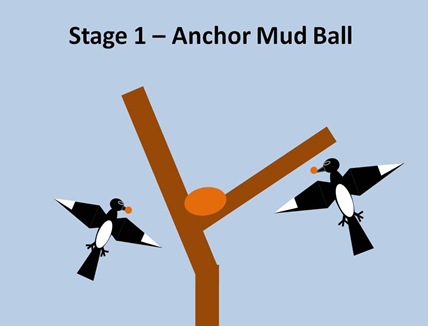

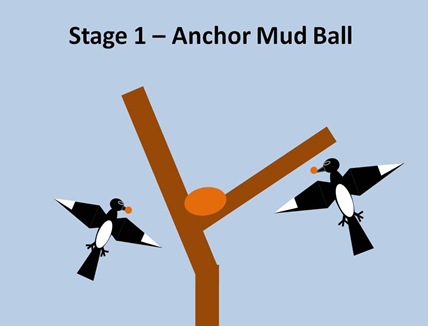

Magpies- male and female- spend 6 or 7 weeks diligently building their nests, a process which involves 5 stages. Stage 1 is the Anchor Stage, in which a clump of mud is transported up and packed into a base for the nest.

Stage 2 is the Superstructure Stage. The birds build up the base and roof of the nest, as well as the frame of the sides. But the sides are left largely open in this stage, probably for interior access during succeeding stages.

Stage 2 is the Superstructure Stage. The birds build up the base and roof of the nest, as well as the frame of the sides. But the sides are left largely open in this stage, probably for interior access during succeeding stages.

In stage 3 a mud bowl is built inside, and atop the base of, the nest.

In stage 3 a mud bowl is built inside, and atop the base of, the nest.

After the bowl is built, it is then lined (stage 4) with grasses, tiny rootlets, hairs and other fine materials the birds find.

After the bowl is built, it is then lined (stage 4) with grasses, tiny rootlets, hairs and other fine materials the birds find.

Finally (stage 5) the sides are built out and filled in, leaving only one or two small side entrances, which are small enough to keep out larger predators.

Finally (stage 5) the sides are built out and filled in, leaving only one or two small side entrances, which are small enough to keep out larger predators.

Magpie nests aren’t just some slapped-together bunch of twigs; they’re carefully architected and painstakingly crafted with a level of attention and care comparable to that of a beaver’s den.

Magpie nests aren’t just some slapped-together bunch of twigs; they’re carefully architected and painstakingly crafted with a level of attention and care comparable to that of a beaver’s den.

Magpies nest just once/year, though they’ll sometimes start again if the first attempt fails. Mating usually, but not always, takes place in the nest and is pretty quick- less than a minute. Females lay (usually) 6 or 7 eggs, which they incubate for 2.5 weeks, during which time the male brings all of her food. After hatching, the nestlings start flying after about 3 or 4 weeks, and leave the nest after 2 months.

PG-13 Side Note: Male magpies, like most male birds, don’t have penises. Most birds- male and female- have a single anal-genital opening called the cloaca, used for passing waste, ejaculating semen, and laying eggs. Magpies mate by presses cloacas together, which in order to accomplish the male must get his tail under the female’s.

Tangent: Like most people, I was a bit grossed out when I first learned the details of avian anal-genital anatomy. Over time though, I’ve come to admire the engineering simplicity of their “architecture”. If you think about it, we mammals sport a rather complex anatomical array to achieve the same basic functions, a thought that’s almost certainly occurred at some point or other to every long-distance male cyclist.

You’ll sometimes hear BTW, that no birds have penises, but this isn’t true. Ducks and ostriches are 2 examples of birds that have them.

You may well have seen other impressive nests, of eagles, hawks and owls, but it’s worth noting that many of these nests were former Magpie nests, Many, many birds and even some mammals use abandoned Magpie nests for shelter.

Ravens (pic right- snapped this shot back in May in Arches NP and have been dying to use it) have been observed disassembling Magpie nests- twig by twig- to prey upon nestlings. While Magpies aren’t big enough to stand up to Ravens directly, they’ll recruit other, nearby Magpies to help mob attacking Ravens and drive them off. Magpies employ mobbing behavior not only for defense, but also “offensively.” A common tactic is to mob a larger predator such as an eagle or hawk who’s made a recent kill, in an attempt to distract it and snatch away the kill.

Ravens (pic right- snapped this shot back in May in Arches NP and have been dying to use it) have been observed disassembling Magpie nests- twig by twig- to prey upon nestlings. While Magpies aren’t big enough to stand up to Ravens directly, they’ll recruit other, nearby Magpies to help mob attacking Ravens and drive them off. Magpies employ mobbing behavior not only for defense, but also “offensively.” A common tactic is to mob a larger predator such as an eagle or hawk who’s made a recent kill, in an attempt to distract it and snatch away the kill.

Side Note: In fact back in May I stumbled upon, and blogged about, just such a scene along Wasatch Blvd. My stop spooked the Magpies and allowed the Golden Eagle to escape with its kill- a snake.

Teaser For Next Post

Social cooperation, positioning, alliance-building and even deception are critical parts of the Magpie’s lifestyle and success, but we’ll get more into these aspects in Part 2, when we talk about their brains.

Different Magpies And Where They Come From

There are 2 species of Magpies in the US. Here in Utah, throughout the Intermountain West, and even up into Canada and Alaska, our species is the Black-billed Magpie, Pica Hudsonia.  But if you live in or visit Central California, you’ll notice that Magpies there usually have yellow bills, and often whit-ish markings near the eyes. These are Yellow-billed Magpies, Pica nutalli. (pic right, not mine) The 2 species- like all Magpies- have a common form, with the distinctive gently-curved corvid beak and bristled-nostrils*, long tails (the longest of any corvid) and long (for a corvid, though not for birds in general) legs. The longer legs reflect the amount of time they spend foraging on the ground or hopping among branches; Magpies are capable but unexceptional flyers, and their long tails can be a liability in high winds.

But if you live in or visit Central California, you’ll notice that Magpies there usually have yellow bills, and often whit-ish markings near the eyes. These are Yellow-billed Magpies, Pica nutalli. (pic right, not mine) The 2 species- like all Magpies- have a common form, with the distinctive gently-curved corvid beak and bristled-nostrils*, long tails (the longest of any corvid) and long (for a corvid, though not for birds in general) legs. The longer legs reflect the amount of time they spend foraging on the ground or hopping among branches; Magpies are capable but unexceptional flyers, and their long tails can be a liability in high winds.

*The nostrils of Piñon Jays and Clark’s Nutcracker are exceptions; they’re bristle-free, to avoid clogging with pine-pitch.

All corvid feet BTW, adhere to a common structure: independent, sturdy “tarsals” (i.e. not joined in a common body, like our feet) and strong, grasping toes. The feet are scaled on top, smooth on the bottom.

All corvid feet BTW, adhere to a common structure: independent, sturdy “tarsals” (i.e. not joined in a common body, like our feet) and strong, grasping toes. The feet are scaled on top, smooth on the bottom.

Black-billed Magpies look almost identical Eurasian Magpies, Pica pica, and for about 40 years the generally-accepted story of Magpie evolution was this: They evolved in Eastern Asia, probably somewhere around Korea, and then subsequently spread across Eurasia. A few million years ago, Magpies migrated to the Western US, via Beringia. Subsequent glacial advances narrowed and limited the range of these Magpies to the California coast and Central Valley, and they gave rise to Yellow-billed Magpies. Much more recently, Eurasian Magpies reinvaded Western North America, establishing the Black-billed Magpies we see today.

Black-billed Magpies look almost identical Eurasian Magpies, Pica pica, and for about 40 years the generally-accepted story of Magpie evolution was this: They evolved in Eastern Asia, probably somewhere around Korea, and then subsequently spread across Eurasia. A few million years ago, Magpies migrated to the Western US, via Beringia. Subsequent glacial advances narrowed and limited the range of these Magpies to the California coast and Central Valley, and they gave rise to Yellow-billed Magpies. Much more recently, Eurasian Magpies reinvaded Western North America, establishing the Black-billed Magpies we see today.

It’s a cool story, with multiple migration-waves reminiscent of the stories we’ve heard for bears and bison. Unfortunately it turned out to be totally wrong.

It’s a cool story, with multiple migration-waves reminiscent of the stories we’ve heard for bears and bison. Unfortunately it turned out to be totally wrong.

Probably the single most interesting thing about corvids that you never knew is this: they are apparently Australia’s most successful export. DNA evidence suggests that the original proto-crow evolved in and emigrated from Australia something like 25-30 million years ago*. Today corvids are wildly successful worldwide, on every continent except Antarctica.

*Around the same time primates appeared. Remember this: we’re coming back to it in Part 2.

Magpies, genus Pica, do indeed seem to have evolved from corvid ancestors in or around Korea, but the parallels with the “old” story end there. Korean Magpies, Pica pica sericea*, are the most distantly-related to all other Magpies and seem to have diverged earliest. Magpies from Western Europe across Siberia to Kamchatka are closely-related and a single species.

But Black-billed Magpies, despite outward appearances, are much more closely-related to Yellow-billed than to any old world Magpies, and it now appears that the 2 North American species are both descended from a common founder population of Eurasian Magpies that migrated to North America 3 or 4 million years ago via Beringia.

But Black-billed Magpies, despite outward appearances, are much more closely-related to Yellow-billed than to any old world Magpies, and it now appears that the 2 North American species are both descended from a common founder population of Eurasian Magpies that migrated to North America 3 or 4 million years ago via Beringia.

*In light of the recent DNA evidence, this guy will probably be reclassified from subspecies to species, P. sericea.

Side Note: This summary omits the “Magpies” of other genera, such as Cissa, Urocissa and Cyanopica, which include the various Magpie species of Southeast Asia and a few other Old World locales. These birds are more distantly-related to Pica, and appear to have evolved their “Magpie-ness”- long tail, etc.- independently, although they do appear to be more closely-related to Pica than are crows or ravens. (Pic right = Formosan Blue Magpie, Urocissa caerulea, not mine, because, uh… I’ve never been to Taiwan.)

Side Note: This summary omits the “Magpies” of other genera, such as Cissa, Urocissa and Cyanopica, which include the various Magpie species of Southeast Asia and a few other Old World locales. These birds are more distantly-related to Pica, and appear to have evolved their “Magpie-ness”- long tail, etc.- independently, although they do appear to be more closely-related to Pica than are crows or ravens. (Pic right = Formosan Blue Magpie, Urocissa caerulea, not mine, because, uh… I’ve never been to Taiwan.)

Tangent: I hate googling for pics, because at least 1/2 the time my image search turns up really weird stuff that either a) I’d be embarrassed if Awesome Wife walked in and saw me looking at or b) an image is so weird I just know it’s going to give me freaky dreams, or c) both, as was the case here. This is the first image hit I had for “Formosan Blue Magpie.” Really? This came up first? Tell me again how Google works?

Tangent: I hate googling for pics, because at least 1/2 the time my image search turns up really weird stuff that either a) I’d be embarrassed if Awesome Wife walked in and saw me looking at or b) an image is so weird I just know it’s going to give me freaky dreams, or c) both, as was the case here. This is the first image hit I had for “Formosan Blue Magpie.” Really? This came up first? Tell me again how Google works?

While we’re on the topic, all Jays in the New World- Piñon, Scrub, Stellers, Blue, etc.- appear to be a monophyletic family, more closely-related to each other than they are to crows, ravens or magpies.

Magpies And People

Another interesting thing about Magpies is that they seem to have adapted various ancestral behaviors to humans and human habitat. One example is what are called protective nesting associations.  Magpies have long been known to nest close to- and even in the same tree as- hawks and ospreys. It’s thought that the presence of such raptors might help keep nesting areas clear of prospective nestling/egg predators, and raptors, strangely, are often tolerant of smaller birds nesting close by. (Though what they “get” in return for their tolerance I’m not clear.) Over the last century+, Magpies seemed to have transferred this behavior to human habitats, favoring nesting sites in tall trees in and around ranches and suburban neighborhoods. Humans generally keep their habitats (at least somewhat) clear of snakes, rats, raccoons and other threats, and so the association may make our neighborhoods somewhat safer nesting sites for them.

Magpies have long been known to nest close to- and even in the same tree as- hawks and ospreys. It’s thought that the presence of such raptors might help keep nesting areas clear of prospective nestling/egg predators, and raptors, strangely, are often tolerant of smaller birds nesting close by. (Though what they “get” in return for their tolerance I’m not clear.) Over the last century+, Magpies seemed to have transferred this behavior to human habitats, favoring nesting sites in tall trees in and around ranches and suburban neighborhoods. Humans generally keep their habitats (at least somewhat) clear of snakes, rats, raccoons and other threats, and so the association may make our neighborhoods somewhat safer nesting sites for them.

Another example is hunting/scavenging. If you know much about ravens, you may well have heard that they often follow hunters (and maybe even gunfire) in the Fall, hoping to scavenge recent kills/entrails. It’s thought that this represents a transference of an ancient behavior of following, tracking and showing up at recent wolf-kills, and in fact there’s evidence that Ravens will call wolves to dead carcasses, so that the wolves will open the carcass, something the raven cannot achieve with its bill.

Another example is hunting/scavenging. If you know much about ravens, you may well have heard that they often follow hunters (and maybe even gunfire) in the Fall, hoping to scavenge recent kills/entrails. It’s thought that this represents a transference of an ancient behavior of following, tracking and showing up at recent wolf-kills, and in fact there’s evidence that Ravens will call wolves to dead carcasses, so that the wolves will open the carcass, something the raven cannot achieve with its bill.

It turns out that Magpies have long had such an association with coyotes, following them and relying on them to open carcasses. And like ravens, Magpies may have transferred this association to humans- not so much in the form of hunting, but in the form of road-kill. If you’ve driven anywhere in the Western US you’ve probably seen Magpies feeding on dead deer and elk along roadsides. Without the crushing/tearing impacts of motor vehicles, Mapgies would be unable to access most of the flesh in such thick-hided dead animals.

It turns out that Magpies have long had such an association with coyotes, following them and relying on them to open carcasses. And like ravens, Magpies may have transferred this association to humans- not so much in the form of hunting, but in the form of road-kill. If you’ve driven anywhere in the Western US you’ve probably seen Magpies feeding on dead deer and elk along roadsides. Without the crushing/tearing impacts of motor vehicles, Mapgies would be unable to access most of the flesh in such thick-hided dead animals.

Oh, I almost forgot about the pecking-at-sores thing. Yes, Magpies really do this, though not often. More commonly they perch on the backs of both livestock and wild ungulates, feeding on ticks. In times of food-duress however, they’ve been known to peck at, enlarges and feed upon the sores caused by such ticks. (In this, I’d again cut them some slack, as it seems to be a stress-induced behavior, maybe analogous to starving humans eating dogs and horses*.)

*I tried horse once, in France, and you know what? It was pretty good. Like steak, but leaner and somehow almost slightly sweet, kind of like buffalo. And no, I’ve never eaten dog! What do you think I am- Hannibal Lecter??

Human habitat associations appear to be expanding the range of Magpies. Ranching has made them more common in the Eastern Great Basin than they are thought to have been historically, and human farms, ranches and suburbs seem to be helping them spread Eastward across the plains.

So Magpies have a lot going on, and are certainly worth checking out. But the coolest thing about Magpies isn’t nest-building or family life or human associations or any of the things we’ve talked about in this post- it’s their brains.

Next Up: Flying monkeys and the parallel evolution of intelligence

Note: Special thanks to reader and fellow Awesome Nature Blogger KB for her kind assistance tracking down Magpie phylogenetic research.

13 comments:

When I was a kid Magpies were viewed as pests and were routinely shot, even though they were protected in 1918. My sense is attitudes toward Magpies have improved as have their numbers.

Thanks for increasing my understanding of this bird. Looking forward to tomorrow's post.

I've always liked the name "Holstein Crows"

Rainbow Spirit

I keep wondering about their tail, and what role it plays. I thought that someone was hot onto the answer to this by studying their flight - but a lit search showed that it was a dead end. Did you find anything about that?

I live at 8000 ft in a conifer forest, and the only time of year when the magpies visit my house is hunting season. Believe it or not, they show up a day or two early (do they have hunting season calenders?). Then, they linger a few extra days before moving to nearby meadows.

Very cool graphics about the nest!

Magpies are really quite amazing. Kind of like teenage males - they like new shiny things and sometimes live off their hosts (parents) and can be real pests. JK. BTW, after those awesome graphics, I tried googling magpie nests but came up with weird results.

mtb w

KKris- I think Magpies are still regarded as pests, particular by the older generation. I was taking one of the nest shots Saturday, and the neighbor (an older woman) came out and started going off about how little she cared for them...

RSP- "Holstein Crows"- good one!

KB- I came across 3 possible explanations for the length of the tail: 1) It helps them fly up or dodge quickly, which might help them in harassing other birds to snatch their food, or weaving in, through and around branches and thickets. 2) It helps them balance when hopping/walking on the ground or branches. 3) It’s a sexual selection thing, indicating some other aspect(s) of health/fitness. (I was a little dubious of this last one, because both males and females have long tales…)

I’ve noticed that many Grackles (Quiscalus) (which I see sometimes down in St. George, as well as Central America when I travel down there), which aren’t corvids and are not closely-related to Magpies, have similar long tails and overall form. A future post idea I have floating around is to figure out what convergent selection pressures (if any) brought about their common morphology.

Researching Part 2 I thought I’d read every clever Magpie story out there, but the showing up for hunting season is a new one!

mtb w- The teenage male analogy is a good one. Interestingly I've heard teenaged males used as analogs for several things, my favorite of which was UFOs: a friend suggested that the only way UFOs could be real was if they were piloted by teenaged aliens, as only that would explain their odd behavior!

Maybe magpies aren't so bad after all. No, that is some really interesting stuff about them. Surprising that they nest in the same trees as some of their predators.

Also, is that a dead magpie that you are taking pictures of?

Layne- yes it was (dead). Click on the Feet photo; the caption at the bottom tells the story.

Awesome nesting graphic. I feel like I just watched a magpie pair nesting in my backyard after viewing that graphic.

Early yesterday evening I heard major magpie commotion in my neighbor's backyard, and saw the neighbor's dog standing over a magpie fluttering on the ground. I hopped the fence, called the dog off and picked up the injured bird which was on his back. He tried flying away but ended up in my yard and on his back again. His wing looked a little bloody right at the "armpit" - the point where the wing attaches to the body. It was too late to call a wildlife rehabilitator, so I made him a box lined with straw and put him in it along with some water and ground seeds and some grubs and kept him indoors for the night. He appeared to be quiet and sleeping with his head tucked to the side when I went to bed, his beak about an inch away from the water dish. I was intending to take him up to Ogden this morning (I'm in SLC) but he died during the night. :( Oh well.

I just came across this blog page, because I was searching for 'magpie nest' and this came up. Love the graphics, info and photos lol. About their tail - I have also wondered why it's so long since they don't seem to fly well with it, tho it's pretty. After years of feeding them at my house in CO, I believe it is for strutting around during the breeding season and sticking it straight up in the air while puffing their body feathers out. They seem to do this in groups, then sometimes I see them get pissy with each other afterwards. Like how deer/elk males who have the biggest antlers usually 'win'. I'm not sure, but this is the only thing I've seen them do with their tails besides flair it out all fancy when landing.

We were fascinated by your article about Maggies nests. My husband and I walk early in the morning and befriended a magpie family- they had a little guy which we named 'Jimmy'. Initially

when he flew to us for some minced meat, his mother & father would go ballistic screeching, and swooping, but after a few times, they started to trust us and joined Jimmy each morning for a little snack. We became very, very fond of these 3 little guys who were so happy to see us each morning- it also made the walk so much more enjoyable. One day though, about 6 months down the track, they did not appear- we were puzzled until I spotted a flattened pile of black & white feathers in the road- it was our Jimmy- we were devastated. Mummy & Daddy bird were despondent and hardly ate anything for days- that was 5 months ago- and I'm happy to say, that breeding time is here again and we are hoping for a little Jimmy 11 or a Gemma -we do hope that they still trust us enough with their new babies.

I have been watching the strangest thing - for the past few days three magpies working together on one nest! Anyone else observe anything like this?

Have a pair nesting in the blue spurce in my backyard. I've had tons of time, quarantined at home due to Covid-19. Now, I'm unemployed as a result= more time to observe the magpies at work. They have 4 fledglings now and are stellar parents to say the least. All of their behavior is exactly as you described, from nest building on. They are omnivores that's for sure and I've seen them attack and kill baby rabbits and even morning doves (once!). Thanks for the great read.

Post a Comment